In Practice

Sculptural Sweets

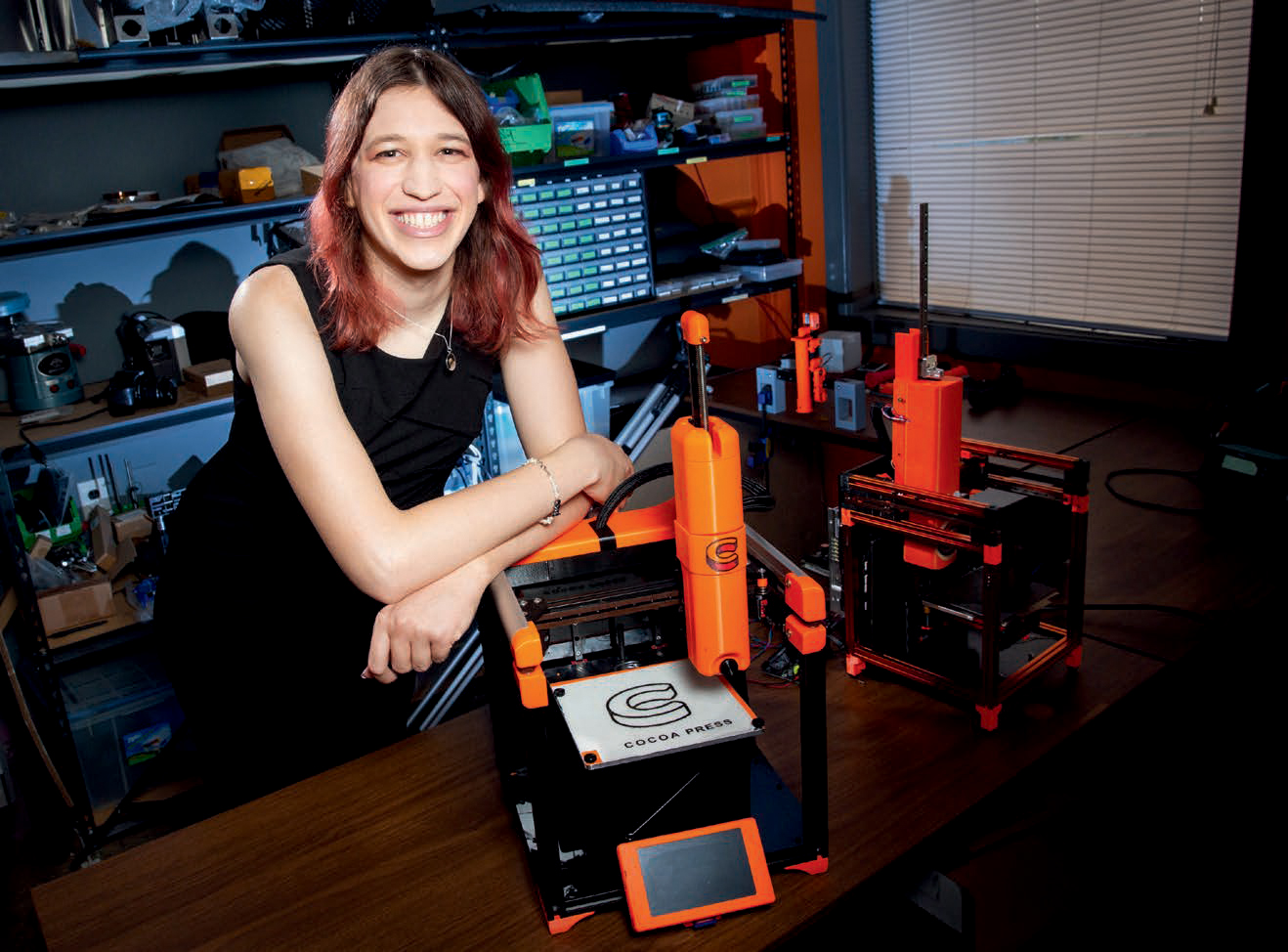

In a few short decades, 3D printing has gone from unique to ubiquitous. It’s used nearly everywhere, from making toys and gadgets in classrooms nationwide to manufacturing new parts on the International Space Station. Ellie Weinstein (MEAM ’19) has a different venue in mind for this emerging technology, however: the kitchen.

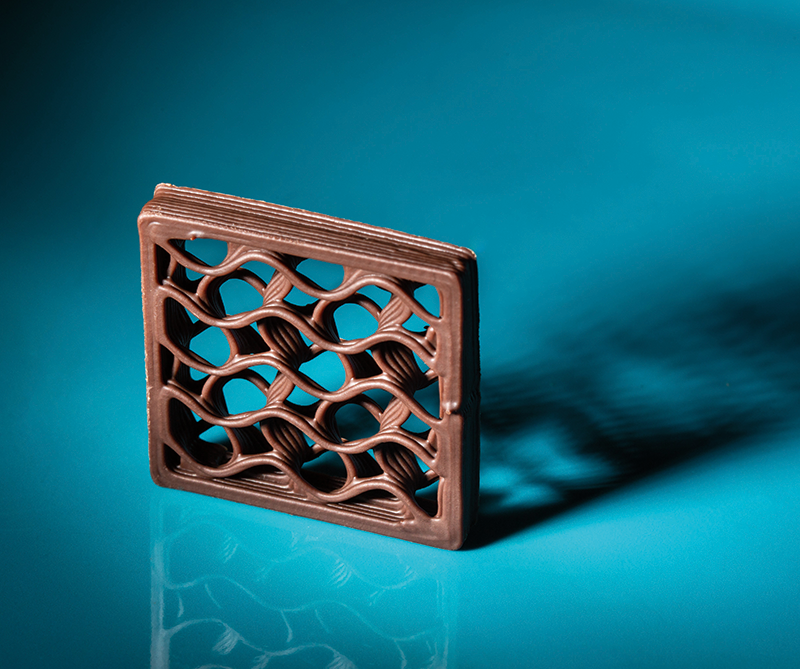

Instead of printing plastic or metal, Weinstein is tweaking the technology to print chocolate in elaborate shapes and patterns. Her company, Cocoa Press, which she founded in 2019 as an undergraduate at Penn Engineering, makes confectionaries out of delicate, lace-like chocolate strands that crisscross one another as they are laid down by a modified printer, gradually building up a lattice of edible artwork.

“3D printing lets you create intricate textures that are not possible to mold,” says Weinstein. “The printed chocolates melt in your mouth in a different way than a solid or hollow molded shape does.”

Printing chocolate as a business wasn’t Weinstein’s original goal. Her idea initially started as a hacked-together high school project in 2014. Once at Penn, Weinstein kept tinkering and improving the device as a hobby, incorporating what she gradually learned while working on her degree in Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics. After increasingly positive feedback on her idea, she started to realize its commercial potential, taking entrepreneurship classes while fine-tuning her 3D printer for her Senior Design project.

“It was perfect. Our team had access to a machine shop to fabricate all the parts, and we would reach out to professors for help with technical roadblocks. We had access to mechanical engineering experts for the device itself, professors working in thermodynamics for figuring out how to precisely heat the chocolate and fluids professors to help troubleshoot how the chocolate flows,” she recalls. After graduation, financial support from Penn Engineering’s Miller Innovation Fellowship and the Pennovation Accelerator (a program that helps to jumpstart local businesses) helped her create the devices and confections that she now sells commercially.

A Sticky Problem

Printing a material like chocolate isn’t as easy as it sounds. As a material, it’s finicky: In addition to mixing just the right ratios of cocoa, sugar and fats, making successful solid chocolate requires heating and cooling the mix at just the right temperatures and times, which forces fatty acids within it to crystallize into predictable structures. There are also storage issues to consider. If the concoction isn’t heated correctly, the end product will eventually “bloom,” leaving an unsightly (although harmless) powdery substance on its exterior as fat content comes to the surface.

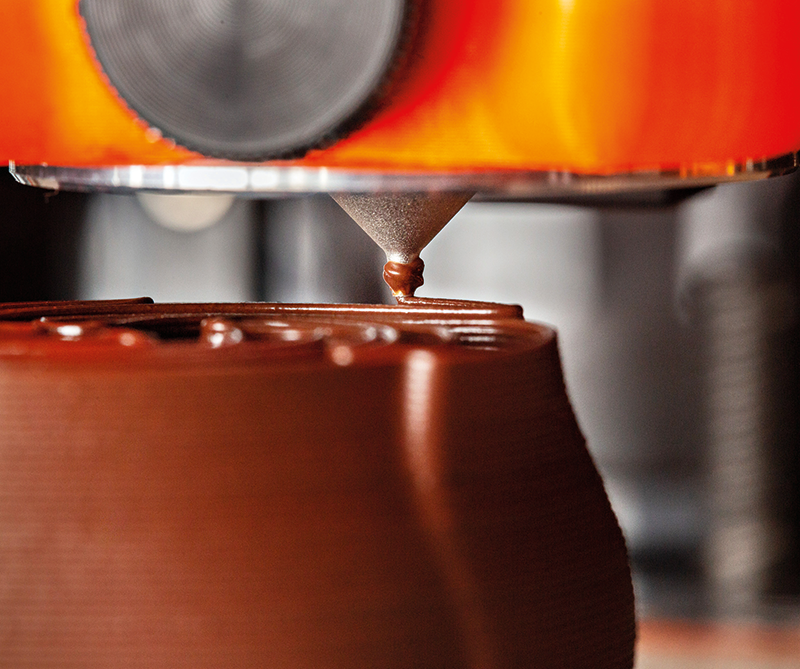

“The hardest part is regulating the temperature within a narrow range as the chocolate prints,” she says. “Stock 3D printers are not meant for precise temperature control, and so we’ve had to do a lot of custom modifications to get that to work.”

The nozzle of the printer, for instance, has to be able to warm chocolate held in a stainless steel cartridge just enough to turn it into a gel-like consistency, so a plunger can then squeeze it out into a fine line. Once the chocolate is laid down, the printer’s bed has to instantly cool that line back down again to maintain its shape. If that weren’t enough, Weinstein says, all parts of the machine have to be food safe, easy to disassemble and simple to wash.

Temperature Check

In previous iterations, Weinstein got around some of the temperature issues by surrounding the printer with a carefully controlled environment — effectively a high-tech mini fridge — ensuring that the extruded chocolate stays firm and can build up complex 3D layers.

At the moment, however, she’s working to make the machine simpler, cheaper and easier to use. Weinstein is experimenting with adding new types of chocolates that are more forgiving, allowing users to print them in a broader range of temperatures. She’s also close to releasing a countertop model that doesn’t need a complex enclosure, an improvement that will lower the cost of the assembled device by more than 60% (a build-your-own-kit model will also be avail- able for even less, she adds). Weinstein hopes that this move will make her device more broadly accessible to consumers, putting it within reach of independent pastry chefs and adventurous home cooks.

“A lot of what I see as the core of engineering is just breaking down these complex problems into smaller ones. And often, when you Google them, you’ll find someone has already solved most of those smaller problems,” she says. “It’s just a matter of putting them all together in the right way.”

Text by David Levin / Photos by Leslie Barbaro